By Richard Williamson, art dealer and founder of London gallery McKay Williamson

There is a fascinating paradox at the centre of the art world: art is a deeply human delight, yet it has this reputation as the preserve of the privileged. This is possibly related to the fact that while most children believe they’re creative, few adults do.

Unfortunately, this puzzling disconnect spills into public policy, with public school art budgets under constant threat, as if they’re defunding yachting lessons. But research shows that art can improve our world, that seeing visual artwork actively lowers stress and can improve our mood in just a few minutes.

So why does our society seem to resist something that’s so clearly beneficial?

One possible explanation is that the art world has invented a labyrinth of language around art, which most people find confusing at best and intimidating at worst. It is partly this language which gives the art world an elitist reputation and undermines our sense of connection to it.

Consider this description from a prominent New York gallery: ‘[the artist] deploys abstracted text expressions in conceptual installations rich with acerbic social critique and a post-pop aesthetic.’ What does that even mean?

What if there is a simpler approach to speaking about art that not only accepts that art is personal and subjective but also respects art history? What if, whenever you see a piece of art, the only ‘art world’ vocabulary you needed were Narrative, Nuance and Novelty. Here’s how it works:

The Power of Narrative

The first of these pillars is narrative. From cave paintings and ancient hieroglyphs to the modern age, art is the visual fabric of human history. It’s meant to say something.

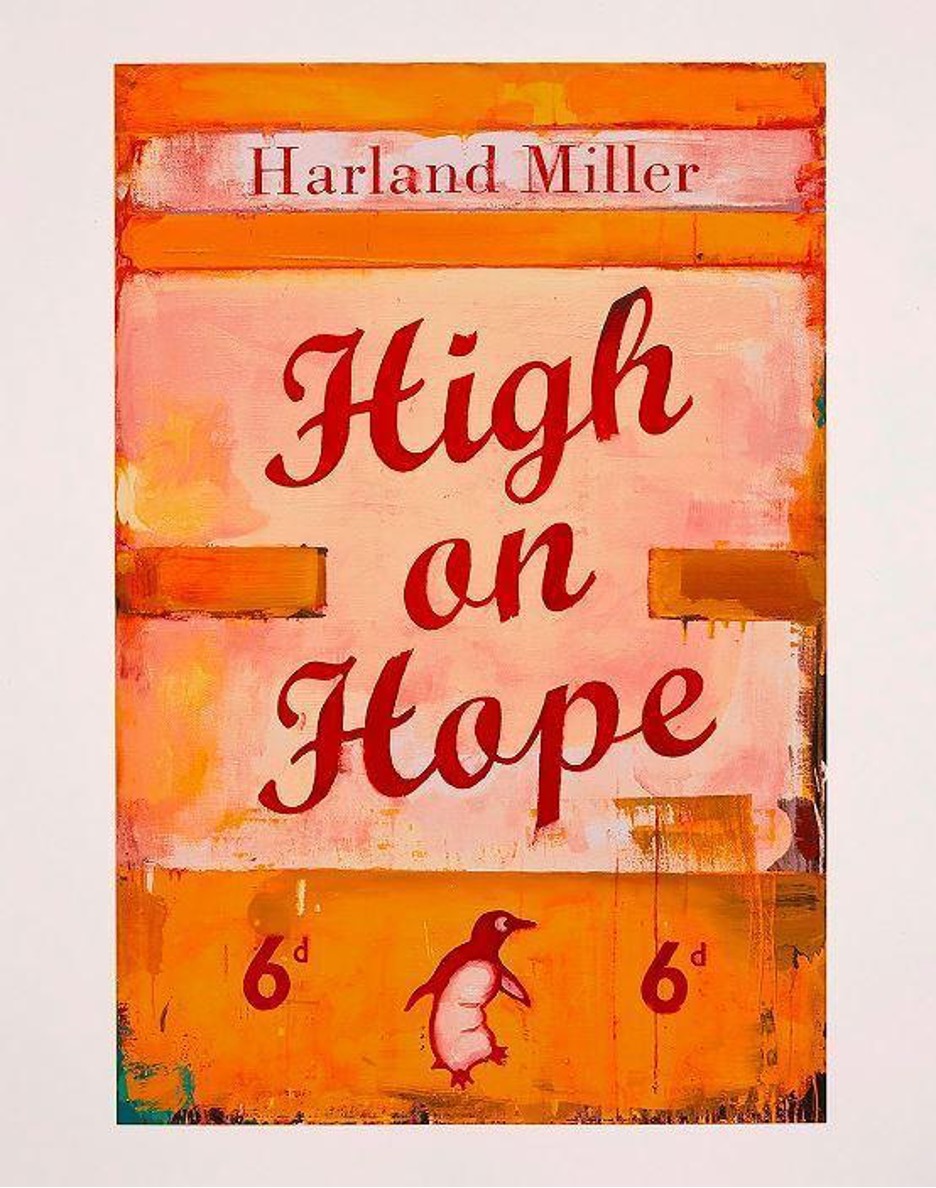

For a contemporary example, look at Harland Miller’s High on Hope (2019), pictured above. Initially, this painting seems joyful and optimistic. But the word ‘high’ can mean elevated or intoxicated, suggesting a dual meaning. Perhaps, the narrative of this work infers, we are so addicted to hope for the future that we forget to embrace the here and now. In truth, Miller intended both interpretations, which is what gives High on Hope such a profound degree of narrative.

When looking at a work of art, ask yourself, what is it saying? Good art always has narrative.

Uncovering Nuance

Nuance invites us to ask, “What if my kid could make that?”

To illustrate this point, here’s a piece of art without much nuance. Yes, with a pair of scissors and a can of spray paint, your kid could make a Banksy. But they’d have to think of it first.

The interesting nuance in Banksy’s work lies in doing so much with a stencil. Love is in the Air was found in Beit Sahour, in the West Bank, which helps to explain why it’s so powerful.

A piece of art without much nuance arguably needs to compensate with greater levels of narrative or novelty, which this one does. Some experts disagree. But the point is that no one needs a specialist art vocabulary to have the debate.

The Novelty Factor

The final pillar in this art decoding system is novelty – how original is the art?

After language, one of my biggest criticisms of the art world is that it has started to prize novelty far more than narrative and nuance. Novelty is important but not paramount.

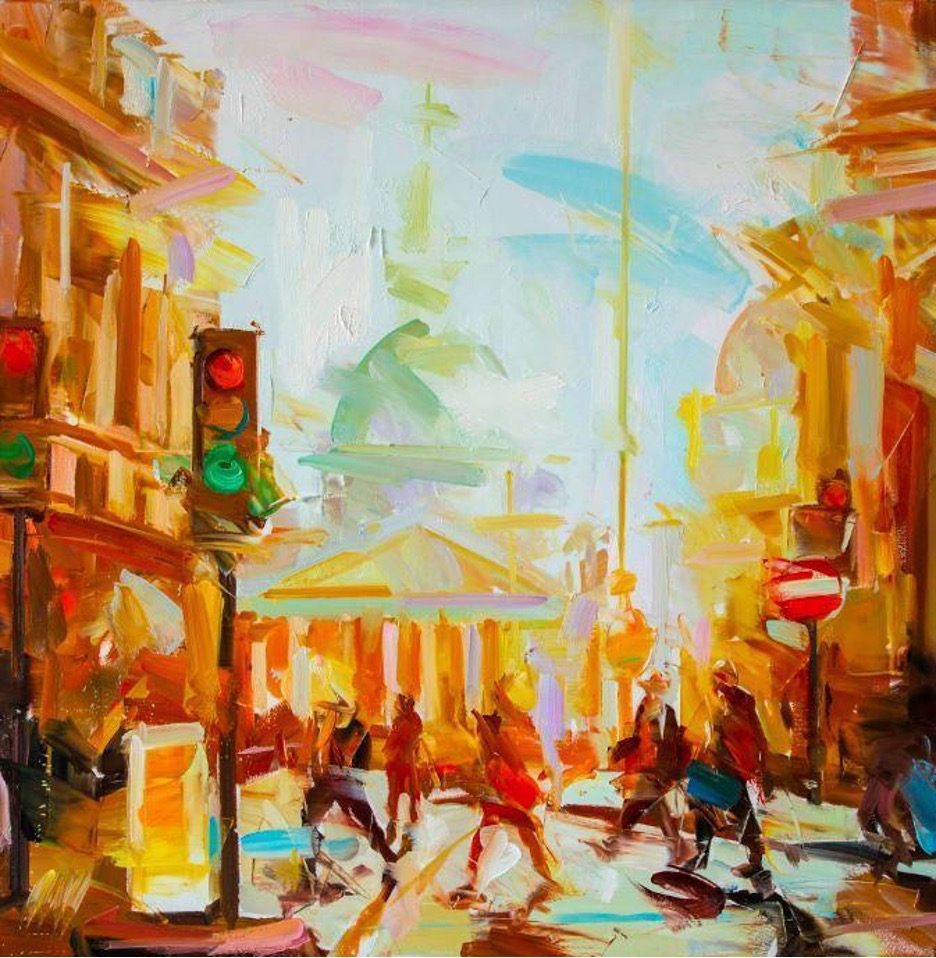

Paul Wright’s Golden Walk (2022), from his exhibition London for Londoners, is a great example of novelty. St Paul’s Cathedral would usually be the focus of this painting’s composition. But with the restrained use of colour, here, it’s an afterthought. That touch of novelty transforms it from a hackneyed cityscape into a whimsical expression, with a heavy dose of nostalgia for every Londoner who has ever hurried along Fleet Street, late for a meeting.

It also proves that a healthy dose of novelty does not require the absurdity we sometimes see, such as Damien Hirst’s famous dots masquerading as an original idea.

Language as the key

When Succession fans discussed the final episode, they probably didn’t use specialist film-making language like jump-cuts or dissolves. They spoke naturally. It’s an important point when it comes to making the art world more accessible.

To be fair, all these points are small examples of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis from linguistics, which says that the words we use around a subject help structure our brain function around that topic. In short, words matter.

Of course, the key to loving art is the emotion we feel, not the words. By using simpler language, we invite more people into a relationship with art with the sort of fervour that rivals the watercooler discussion of any drama series finale.